Product Description

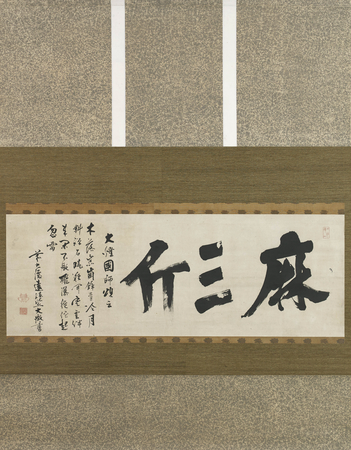

7197 Daitetsu Sōto (1765-1828), the 430th abbot of Daitoku-ji Temple, Kyoto

A kakemono (hanging scroll) painted in ink with calligraphy

Inscribed:

Masangin (Three pounds of flax)

*Daito Kokushi said this: In utter coldness as if the wood has pieced into the rock, I sit under the slanting moon to meditate until dawn overcoming hindrances, chilly clouds are accompanied by penetrating quietude, the gushing splash of a waterfall is heard somewhere along with sudden thundering.

*Allegedly a direct quote from Daitō Kokushi (1282-1338) the second patriarch and founder of Daitokuji Temple, Kyoto.

Seals:

Right: Manji Hōju-ichi

Left, upper: Daitetsu

Left, lower: Kaan dojin (The snail studio, a man of Tao)

Japan 18th/19th century Edo period

Dimensions:

Scroll: H. 57″ x W. 42¾” (144.5cm x 108.5cm)

Painting: H. 15″ x W. 40¾” (37.7cm x 103.5cm)

Daitetsu Sōto (1765-1828) was the 430th abbot of Daitoku-ji Temple, Kyoto. Daitoku-ji was founded in the early 14th century and is the Headquarters of the Rinzai sect of Zen Buddhism.

Work by the artist can be found in the collection of: The Spencer Museum of Art, The University of Kansas, USA.

Masangin appears in an early Buddhist text ‘The Gateless Gate’ by Wumen Huikai (1183-1260) a famous Chinese Zen master from the Song period who compiled and commented on a collection of 48 Kōan.

In koan #18 Dongshan Liangjie (807–869) or Tozan Ryōkai (in Japan) says:

A monk asked Tozan: “What is Buddha?”

Tozan replied: “Masangin!” (Three pounds of flax)

At that moment Tozan was carrying three pounds of flax, therefore he could not indicate anything else. In fact he is saying that the question is wrong and if you ask a wrong question you will get a wrong answer as it is impossible to say what the experience of being a Buddha (enlightened) is.

However, he is compassionate and polite and chooses not to say: “You idiot! A question about Buddha is not to be asked – it is an experience without any explanation, an experience beyond the mind.” He simply gives an absurd answer: “Masangin!”

Zenga (Zen painting) is a form of teaching: in calligraphy the most common subjects are Zen poems and conundrums. The style of the brushwork is dramatically bold, seemingly impetuous and bluntly immediate in effect. The transition from mind to paper is spontaneous and finished works distill the essence of the Zen experience with simple strokes of the brush. The logic-destroying potential of a Zen Kōan (riddle) becomes visible in the movement of roughly brushed calligraphy.

Kōan consist of anecdotes, conversations with and sayings of the great patriarchs, some legendary and some biographical. They were designed to serve the pupil as a tool in his own religious practices and to eventually lead him to enlightenment.