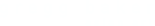

Product Description

A bronze kakebotoke (hanging plaque with a Buddhist image) adorned with a figure of Jūichimen Kannon (Eleven-Headed Bodhisattva) seated on a lotus base

Japan 13th/14th century Kamakura Period

Dimensions:

Diam. 36cm x D. 6cm (14¼” x 2½”)

Figure H. 20cm x W. 12cm x D. 6cm (8″ x 4¾” x 2½”)

Kakebotoke (hanging Buddha) are votive plaques (generally circular), symbolising mirrors, which represent the sacred body of kami (Shinto deities), and are adorned with repoussé or cast images most frequently of Buddhist deities. They originate from the practice of Shinbutsu-shugo (syncretism of kami and buddhas) which was established in the Heian period. One of the few forms of Buddhist art unique to Japan, they can be found both at Shinto shrines and Buddhist temples and are presented as offerings to safeguard the compound and to ensure the prosperity of the Buddhist faith. In the Buddhist context they were hung from the eaves above the main entrance to an Image Hall, or above the frieze rail between the outer and inner sanctums of the shrine for the deity that protected the temple compound. They may also be used to represent hibutsu (hidden Buddha) which are not generally on show to the public.

From its simple formation as well as its wear consistent with age, the figure of Jūichimen Kannon (Sk: Ekadashamukha Avalokiteshvara) on this plaque shows minimal features. The head is adorned with simplified, almost abstract forms of small heads and both arms are in particular positions, namely the lowered right hand indicating the yogan-in (the granting of wishes) mudra and raised left hand as if holding a byo (vase), suggest that this deity is the Jūichimen Kannon.

For similar, comparable images of Jūichimen Kannon in simplified forms as kakebotoke, see The Museum of Shiga Prefecture Biwako-Bunkakan ed., Kakebotoke no sekai [The world of hanging plaques with Buddhist images], (Japan, 1997), no. 14 (dated 1252, the Kamakura period, a private collection, Kyoto); no. 62 (one of the figures, Heian-Momoyama period, Hando Shrine, Shiga); no. 66 (one of the figures, Kamakura-Muromachi period, Tamao Shrine, Shiga).

Kannon (Avalokiteśvara), the bodhisattva of mercy is one of the most widely worshipped Buddhist divinities in Japan. Kannon personifies compassion and is said to remain in this world to help mankind find salvation. The name Kannon, meaning ‘watchful listening’ is the shortened version of his original title, Kanzeon, meaning ‘the one who constantly surveys the world and saves sentient beings upon hearing their sounds of suffering and cries for help’. The byo, containing the water or nectar of life, is a characteristic attribute of Kannon and seen here symbolises the nectar of his compassion.

Kannon manifests himself in many different forms, one of the oldest and most representative of these is Jūichimen Kannon, an esoteric form of the Bodhisattva who embodies the compassion of all Buddhas and became widely employed in tantric visualisations. In Japan, belief in the power of Jūichimen Kannon is recorded from Nara period (710-794).

According to legend, Kannon vowed never to rest until he had freed all sentient beings from saṃsāra (process of birth and rebirth). Despite strenuous effort, he realised that still many unhappy and wicked beings were yet to be saved. After struggling to comprehend the needs of so many, his head split with grief into eleven pieces. Seeing his plight, Amida Buddha (Amitābha) transformed those 11 pieces into eleven heads with which to hear the cries of the suffering. He placed them on Kannon and topped them all with his own image.

The eleven small heads atop the Jūichimen Kannon symbolise his multifarious capacities in his merciful mission of saving sentient beings. They are also believed to dispel the eleven delusions, the fundamental causes of human agony, and guide people to the eleven virtues of Buddhahood, including enlightenment. The positioning of the heads indicates that the elevated head of the Buddha rises above the others – the iconography evokes the ten stages of the bodhisattva’s path towards enlightenment with the Buddha, from whom Kannon emanates, as the final result. The encapsulation of these processes into one image shows the presence of all within the bodhisattva and suggests the fully enlightened bodhisattva as the ideal.

For other examples of kakebotoke see:

Anne Nishimura Morse et. Al. eds., Object as Insight, Japanese Buddhist Art and Ritual, Katonah Museum of Art, p. 46-47, pl. 9/10.

Nara National Museum, Bronze Sculpture of the Heian & Kamakura Periods (Special Exhibition), (Kyoto, 1976), p. 49-53

For more about kakebotoke and further examples, see Naniwada Toru, Nihon no bijutsu (Art of Japan), No. 284 Kyozo to Kakebotoke (Votive Buddhist mirrors and plaques), (Tokyo, 1990).