Product Description

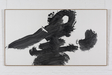

7348 Yūichi Inoue (1916-1985)

Shoku (Belonging)

Ink on paper, framed

Sealed Yūichi

Dated 76.1.31

Dimensions:

Painting: H. 119.7cm x W. 219.7cm (47¼” x 86¾”)

Frame: H. 122cm x W. 221.7cm (48¼” x 87½”)

Provenance: Acquired by the previous owner from Japan Art, Frankfurt, Germany

Published: Masaomi Unagami ed., YU-ICHI, Catalogue Raisonné of the works 1949-1985, Vol. 2 1970-1976, UNAC Tokyo, (Tokyo, 1998), no.76015

Yūichi Inoue (1916-1985) was born in Tokyo the son of a bric-a-brac dealer. In 1935 he graduated from Tokyo Prefectural Aoyama Normal School (present-day Tokyo Gakugei University) and almost immediately began working as an elementary school teacher at Yokogawa National School, Tokyo. Although he always aspired to become a painter, Inoue was lacking the means to attend Art College. He therefore took evening painting classes and later turned to sho (calligraphy) due to its inexpensive materials and less formal instruction. In 1941 Inoue began to study calligraphy under the renowned modernist calligrapher Ueda Sōkyū (1899-1968) and joined his master’s avant-garde calligraphy group Keiseikai.

Ueda himself came from a modernist tradition of avant-garde calligraphers advocating the study of kanji (Chinese characters) by old Chinese masters, while at the same time being aware of contemporary international art movements. The emphasis of Ueda Sōkyū and the Keiseikai group was on the emotional expression of the self at the moment of writing. According to Ueda it is more embarrassing for a calligrapher to lack heart than technique.

In March 1945 Inoue was on night duty at the Yokokawa National School where 1,000 people were taking shelter from a bombing raid by the American air force. The school was engulfed by flames and Inoue was left as the sole survivor. This tragic near-death experience left him deeply scarred and he later described his ordeal in the calligraphic piece entitled Ah! Yokokawa National School, now in the collection of Unac Tokyo Inc.

‘The town plunged into darkness is transformed into an incandescent sea…. All Kōto-ku is hell fire’ he begins. ‘A thousand refugees have no shelter and there is no exit.’ Buried all night in a heap of corpses, Inoue concludes, ‘At dawn, the fire is out. Silence is all. No cries’.

The horrors of war led Inoue to dedicate his existence to the study of avant-garde sho and its promotion through journals such as Shonobi edited by Shiryū Morita, under the leadership of Sōkyū Ueda. He also became fascinated by modern western art and was regularly informed about action painting, abstract expressionism and the work of ground-breaking artists such as Franz Kline (1910-1962), Mark Tobey (1890-1976) and Jackson Pollock (1912-1956) by the pages of the Bokubi journal first published in 1951 by Shiryū Morita. Inoue also befriended cultural emissaries such as Isamu Noguchi (1904-1988), the international avant-garde artist Saburō Hasegawa (1906-1957) as well as various artists from the Gutai group.

In 1952 Inoue along with four other disciples of Sōkyū Ueda; Shiryū Morita (1912-1999), Eguchi Sōgen (1919-) Sekiya Yoshimichi (b.1920) and Nakamura Bokushi (dates unknown) left Keiseikai to found the avant-garde calligraphy group Bokujinkai. The group’s activities were documented in its journal Bokujin edited by Inoue until its 50th issue. The group’s goals were to liberate sho from orthodox conventions, to present it within a global perspective and to establish it as a contemporary artistic medium. The main emphasis was on individual study and unrestricted expression and so the group members refused to participate in large exhibitions or organisations in Japan.

Inoue along with the rest of the Bokujinkai calligraphers abandoned traditional sho materials. This experimentation meant substituting the traditional fude (brush) with cardboard, sticks, hemp-palm and broom sized brushes. Sumi (ink) was also replaced with mineral pigments, oil paint, enamel and lacquer while canvas, wood, ceramic and even glass were used in place of washi (paper). Although their methods were totally innovative, the group pursued a rigorous re-evaluation of the fundamentals of ancient calligraphy and the timeless qualities of the calligraphic line from a contemporary, universal point of view.

These avant-garde calligraphers were not overly concerned that their renderings of kanji characters were legible or whether they had used a character at all. For the calligrapher the process of producing work is an existential involvement. The form gradually becomes ‘his’ during the writing and re-writing of the drafts when the initial or generally accepted meaning of the character may be forgotten. In Zen terms, the form becomes the calligrapher’s koan (Zen dictum). The execution of a piece demands total absorption, both physical and mental, a complete giving of the self to the writing. Implicit in the piece is the whole experience the calligrapher goes through from initial spark, through confused wrestling with the line and form, to the absolute commitment of execution.

Writing in his journal Inoue proclaimed ‘Turn your body and soul into a brush… No to everything! The hell with it! Paint with all your strength – anything, anyhow! Spread your enamel and let it gush out! Splash it in the faces of the respectable teachers of calligraphy. Sweep away all those phonies who defer to calligraphy with a capital C… I will bore my way through, I will cut my way open. The break is total.’

Unagami Masanomi, The Act of Writing:Tradition and Yū-Ichi Today, Ōkina Inoue Yū-Ichi ten/ Yū-Ichi Works 1955-85, Kyoto National Museum of Modern Art, 1989

However, after losing himself in this exhilarating cosmos of experimentation, of discarding the meaning and forms of kanji, Inoue finally came to understand how marvellous they really were and from around 1957, free from the tradition of sho he devoted himself to action painting while adhering to the original characters so that he was to some extend restricted. Inoue came to terms with the beauty in the form of the kanji, admitting worshiping the fatal nobleness of the Chinese characters.

Despite avant-garde calligraphy’s superficial resemblance to abstract art the abstract within the calligraphic tradition is fundamentally different. An artist, should he choose, can reject or ignore the history of art. The avant-garde calligrapher however, cannot. He is working within a centuries-old discipline combining two visual languages, sho and abstract expressionism to convey deeply felt inner conflict and anguish.

When I write a particular character, I am often asked about the meaning of that character. At that point I usually say something that amounts to what you would find in the dictionary. And yet that is a mere entrance-way and no more. To give an explanation that goes as far as I have worked out with great efforts is impossible.

Inoue Yūichi, September 1977, [SHO] by YU-ICHI ’49-’79, edited by Unagami Masaomi, UNAC TOKYO Co. Ltd, 1980.

Works by the artist can be found in the collections of: The National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo; The National Museum of Art, Osaka; The National Museum of Modern Art, Kyoto; The Muuseum of Modern Art, Gunma; Chiba City Museum of Art, Chiba; Carnegie Institution of Science, Whasington D.C.; Langen Foundation, Neuss; Museum Rietberg, Zurich

Selected Solo Exhibitions:

1965 Galerie Rudolf Zwirner, Cologne

1986 Yūichi: Zeppitsu (Yūichi, Psyché Calligraphy-Parting Thoughts), NEWZ and UNAC SALON Tokyo; Nishinomiya Citizen’s Gallery, Hyogo

1989 Yūichi Works 1955-85, The National Museum of Modern Art, Kyoto; Fukuoka Prefectural Museum of Art, Fukuoka; Niigata City Art Museum, Niigata; The yamaguchi Prefectural Museum of Art, yamaguchi; The Ehime Prefectural Museum of Art, Ehime; Koriyama City Museum of Art, Fukushima

1995 Yūichi:1916-1985, Kunsthalle Basel

Yūichi: Exhibition in Commemoration of the publication of Yūichi Sho-ho, Tianjin People’s Art Publishing House Gallery, Tianjin

1999 Inoue Yūichi – Calligraphy is for everyone, Seoul Art Centre, Seoul

2000 Yūichi Vivant, Chigasaki City Museum of Art, Kanagawa

Yūichi Ali, d’Ac galleria Comunale d’Arte Contemporanea di Ciampino, Italy

2005 Inoue Yūichi, Hangzhou International Calligraphy Festival, China Academy of Art, Hangzou

2008 Kanji Art of Inoue Yūichi, Shi Fang Art Museum, Zhengzhou, China

2010 Yūichi, Tokushima Kenritsu Bungaky Shodokan

2012 Yūichi, Works on Paper, Japan Art, Galerie Friedrich Mϋller, Frankfurt

Yūichi, Ningbo Museum of Art, China

2016 Inoue Yūichi, 21st Century Museum of Contemporary Art, Kanazawa

Selected Group Exhibitions:

1950 6th Nitten (Japan Fine Arts) Exhibition, Tokyo

1954 Contemporary Japanese Calligraphy, The Museum of Modern Art, New York

First Exhibition of Bokujin, Tokyo

1955 Bokujin, Galerie Colette Allendy, Paris; Gallerie Apollo, Brussels

Abstract Paintings – Japan and the U.S., The National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo

First Public Exhibition of Bokujin, Kyoto Munincipal Museum of Art, Kyoto; Ueno Matsuzakaya Gallery, Tokyo

1957 4th São Paulo Art Biennial, São Paulo

1958 Fifty years of Modern Art, Universal & International Fair, Brussels

1959 Documenta II, Kassel

1961 6th Sao Paulo Biennal

The 1961 Pittsburgh International Exhibition of Contemporary Painting and Sculpture, Carnegie Institute, Pittsburgh

1969 Contemporary Art Dialogue Between the East and the West, The National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo

1994 Japanese Art After 1945: Scream Against the Sky, Yokohama Museum of Art, Kanagawa; Guggenheim Museum SoHo, New York; San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, San Francisco

2004 Art and War, The Museum of Modern Art, Gunma, Japan

2005 Zeichen setzen, Gunther Uecker and Inoue Yuichi, Langen Foundation, Neuss, Germany

2011 Inoue Yuichi Sho, University City Art Museum of GAFA, Guangzhou, China

2013 Portrait of a Destroyed City, The Museum of Modern Art, United Arab Emirates

2015 Calligraphic Abstraction, Seattle Art Museum, Asian Art Museum, Seattle

The End of Modernity in Calligraphy: From Yuichi Inoue, Lee Ufan to Zhang Yu, Kuandu Museum of Fine Arts, Taipei