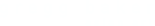

Product Description

7293 A red and black lacquer oi (armour box) decorated with gilt and shakudō (copper and gold alloy) fittings. The front bears a biwa (Japanese lute) shaped bar which when removed reveals four doors enclosing two internal compartments separated by a shelf, the bottom compartment containing a tray. Each side is adorned with elaborate metalwork depicting sprays of kiku (chrysanthemum) and the back has two kiri mon (paulownia crest) above which there is a handle attached to a kiku mon (chrysanthemum crest) shaped plate. These two crests of high-ranking families appear throughout the fittings.

Japan 16th/17th century Momoyama period

Dimensions H. 34½” x W. 23¼” x D. 19½” (87cm x 51cm x 49cm)

The kiri mon (paulownia crest) has always been a symbol of great authority in Japan appropriated by the most powerful shogunates holding command of the country and was originally the private symbol of the Japanese Imperial Family from as early as the 12th century. During the Muromachi period (1333-1573) it was used by the Ashikaga shogunate, a dynasty originating from one of the plethora of Japanese daimyo (shogunates) which governed Japan. During the Azuchi-Momoyama period (1573-1603) the paulownia crest was adopted by the Toyotomi clan led by Toyotomi Hideyoshi (1536-1598) and was used from 1583 until 1598. Later appropriated by the Tokugawa shogunate (1600-1868) it was retained as a symbol of power during the Meiji Restoration from 1868 and it is still used as the emblem of the Japanese government to this day.

Kiku mon (chrysanthemum crest) represents the Emperor of Japan as the symbol of the sovereignty of the State as well as the members of the Imperial Family. It is one of the national seals and a crest used by the Emperor of Japan and members of the Imperial Family.

This piece was originally owned by the Mutsu family, who historically has always been associated with the ruling classes and in the 19th century the head of the family Mutsu Munemitsu (1844-1897) played an important role in establishing the Meiji Government serving as a minister and a diplomat. He was born in Wakayama, the son of Date Munehiro (1802 –1877) a samurai of the Tokugawa shogunate who was active in the Sonnōjōi (lit. Revere the Emperor, Expel the barbarians) movement. This was a Japanese political philosophy and a social movement which derived from Neo-Confucianism and was aiming to overthrow the Tokugawa shogunate during the end of the Edo period. Mutsu Munemitsu joined forces with Sakamoto Ryōma (1836-1867) and Itō Hirobumi (1841-1909) in this aim.

After the establishment of the Meiji Restoration in 1868, Mutsu held a number of posts in the new Meiji government, including that of governor of Hyōgo Prefecture and later governor of Kanagawa Prefecture, both of which hosted foreign settlements. He was head of the Land Tax Reform of 1873–1881, and served on the Genrōin (Chamber of Elders). He conspired to assist Saigō Takamori (1828 –1877) in the Satsuma Rebellion (a revolt of disaffected samurai against the new imperial government) and was imprisoned from 1878 until 1883. While in prison he translated Jeremy Bentham’s (1748-1747) Utilitarianism into Japanese.

After his release from prison, he re-joined the government as an official of the Foreign Ministry, and in 1884 was sent to Europe for studies. Later he became Japanese Minister to Washington D.C. (1888–1890), during which time he established formal diplomatic relations between Japan and Mexico, and partially revised the unequal treaties between Japan and the United States.

On his return to Japan in 1890, he became Minister of Agriculture and Commerce. He was also elected to the House of Representatives of Japan from the 1st Wakayama District for a single term in the 1890 General Election. In 1892, he became Foreign Minister in the Itō Hirobumi cabinet. In 1894, he concluded the Anglo-Japanese Treaty of Commerce and Navigation of 1894, which finally ended the unequal treaty status between Japan and Great Britain.

Mutsu was the lead Japanese negotiator in the Treaty of Shimonoseki, which ended the First Sino-Japanese War (1894-1895). In the wake of an attempt on the life of the Chinese leading negotiator Li Hung-chang (1823 – 1901) by a Japanese fanatic, the Japanese government voluntarily reduced the size of the indemnity it planned to claim from China, and Mutsu famously remarked, ‘Li’s misfortune is the good fortune of the Great Ch’ing Empire’. The Triple Intervention by France, Germany and Russia reversed the gains that Mutsu had negotiated from China in the Treaty of Shimonoseki, and the Japanese public blamed Mutsu for the national humiliation. He resigned from all government posts in May 1896 and moved to Ōiso, Kanagawa, where he wrote his personal diplomatic memoirs Kenkenroku in an effort to explain his views and actions. However, his memoirs were not published until 1923 due to the diplomatic secrets they contained.

Provenance: Previously in the collection of Mutsu Munemitsu (1844-1897) of Wakayama Prefecture, the Minister of Foreign Affairs during the Meiji period and then my descent to his grandson.

Published in Japanese Antique Chests, Hasebe Junichi; Ribun shuppan,1994, p.92, pl.80.

For similar examples see: Kazari in Gold, Japanese Aesthetics Through Metal Works, Kyoto National Museum, 2003, p.166&167, pl. 131, p.170, pl.134