Product Description

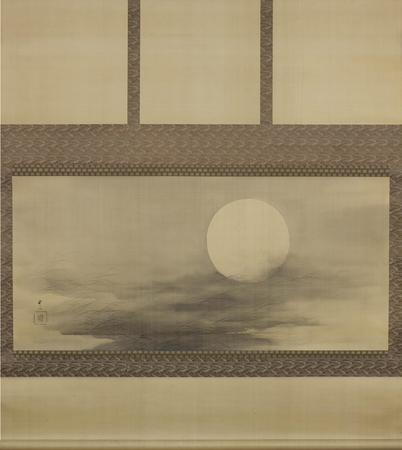

7571 Kodera Untō (1871 – 1930)

A silk kakemono (hanging scroll) painted in ink with the full moon and autumn grasses amongst hazy clouds

Signed: Untō

Seal: Ren

Japan 19th/20th century Meiji/Taishō period

Dimensions:

Scroll: H. 187.5cm x W. 177cm (74″ x 69¾”)

Painting: H. 70.5cm x W. 152cm (28” x 60”)

Now lost the Awasebako (fitted wood box) was inscribed:

Lid: Untō hitsu Mangetsu no zu (Painting of the full moon, painted by Unto), Igeta zō (collection of Igeta family)

Provenance: Igeta family, Japan

Kodera Untō was a master of nihonga (Japanese style painting) active in Nagoya in Aichi prefecture. Untō was born to a feudal warrior family from Owari province and was fond of painting from an early age. He studied Shijō-school painting under Okumura Sekiran (1834-1895) locally and later under Takeuchi Seihō (1864-1942) in Kyoto. The Shijō school was founded in the late 18th century and soon established itself as an important and popular style of nihonga in Kyoto with artists continuing the tradition to the present day. It inherits a great degree of realism through mastery of sumie (ink painting) of the Maruyama-school and a poetic spirit of Nanga (Southern school). The unpainted moon emerges amongst the subtle gradation of ink in this present work showing the artist’s masterful technique and sophistication.

Though the moon’s beauty can be appreciated at any time of year, in Japan doing so is strongly connected with autumn. In haiku poetry the word tsuki (moon) is synonymous with autumn. For the Japanese, whose culture is so connected to the changing seasons and the appreciation of natural beauty, viewing the autumn moon came to be one of the most cherished activities of the year.

Countless works of art in poetry and painting focus on the moon as their major motif, suggesting not only beauty but continuous change and also revival. The full moon which is closest to the autumnal equinox (known in English as the harvest moon) appears larger and brighter than at any other time of year. It is for this reason that the Japanese developed the custom of tsukimi (moon-viewing) in mid-autumn when the harvest moon rises. During moon-viewing, the Japanese make offerings to the moon by placing seasonal crops, plants and full-moon shaped round rice dumplings in a place exposed to the moonlight. Susuki (pampas grass) stalks are also laid out, and these act as a kind of antennae which attract the spirit of the moon to the offerings. As such the full moon and pampas grass are traditionally paired as symbols of autumn in Japanese art and poetry.

This subject matter is also inspired by meisho-e (pictures of famous scenic places), an early tradition from the Heian period (794-1185). The scene is of the Plains at Musashino, a large flat expanse of land west of modern Tokyo, which was frequented during the Edo period inspired by its haunting beauty of the deserted field and spectacular views of Mount Fuji. There is a poem written by Minamoto no Michikata (1189-1239) included in the imperial poetry anthology of c.1265, Shoku Kokinshū (the collection of ancient and modern poems, continued). The translation reads:

The moon finds no hills to hide behind in Musashino

White clouds hang at the tips of the pampas grasses.